ONE

As one

walks by the city of Havana, one senses a process of change of its

traditional appearance, in its best known zones - the Historic Center

and the great Republican area - as well as in certain neighborhoods

and residential areas built in the very beginning of the second half

of the 20th Century. The city changes day by day in front of our very

eyes, it transforms itself. The citizens place protective railings

on their balconies, or enclose with fences of steel wire the small

gardens at the entry of their houses to convert them into garages

or just to isolate themselves from the sidewalk and the street traffic.

Others build walls on the beautiful porches in order to get new space

(a room, a hall, a kitchen or a dining room) for those houses that

get smaller as the family grows larger.

There

are those who decide to set up a small shop to sell coffee, cakes,

biscuits, cold drinks, milkshakes or pizzas of various sorts in front

of their homes or in the common space in the apartment buildings,

and usually place an improvised wooden table on top of which they

put a blender, a big thermos flask, a display case, trays and hand

made signs with the offered products and their prices. Others advertise

some repair services — shoes, fans, watches — or special

services such as barbering, plumbing, masonry or jewelry without noticing

the consequences of this graphic paraphernalia for the ‘image’

or the culture of the city.

Over

the last years people, in an informal way and without hardly any control,

people have been transforming the fronts of their houses and buildings,

or re-shaping corners and empty lots through processes of free intervention

on the public spaces that the city had preserved since its foundation.

Urban laws, norms and regulations, devised to organize any kind of

expansion or transformation are continually being circumvented, not

only by ordinary citizens, but also, though to a lesser extent, by

state companies and ins-titutions. Thus, the city of Havana have started

to blur its architectural outline and features, making the image that

still characterizes it in the eyes of its own citizens and of lots

of visitors from all over the world fade away.

This

is not exclusive for Havana: it happens to the barrios of Bogota,

San Jose, Mexico City, São Paulo, Manila, Jakarta, Istanbul,

Alexandria, Port-of-Spain, Santo Domingo, Luanda, Harare, and hundreds

of other big and small metropolises in our regions of the southern

hemisphere. Since the so-called progress and development — to

some, the well-known ‘modernity’ — are still to

be introduced (from the outside) or to emerge (from the inside) of

our difficult, unstable and feeble economies, people face in their

own ways the challenge of the present and of the future, and to that

end they ‘make’ the decisions they estimate to be the

correct ones, they ‘organize’ their lives individually

and set out to ‘improve’ their material parcels, their

habitats, in a prodigious attempt to gain time — from time.

Bilbao

- PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

Bilbao

- PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

|

On the one hand, ads, colors, symbols and signs,

tents, umbrellas, light roofs, lights, bars, fencings of bricks, stone

or cement, trees, bushes, flowers, horns, television antennae and

lamps, are some of the elements with which the citizens of our ‘developing’

countries design their everyday environment, the one of their barrios

and by extension, that of their cities. Most of the time this takes

place with little creative power, although in some cases occasional

traits of humor and popular wisdom blossom and amuses us making us

feel a little bit more at home, entertained.

On the other hand, the exaggerated and uncontrolled

growth of the urban populations in each country in our regions, due

to the phenomenon of migration and its corresponding informal economy,

contributes to the generalization of a hardly interesting image —

sometimes chaotic, entangled and anarchic — of the city and

the milieu in which thousands and millions of people live. In those

urban spaces, however, a remarkable visual-formal counter-weight becomes

apparent in the more or less ‘attractive’ design of big

warehouses, stores and shopping centers, coffee shops, clubs and hotels

with the corresponding network of graphic information associated with

these buildings, plus a wide range of habitation, banking, judiciary,

educational, entrepreneurial and all sorts of beaurocratic facilities

whose architectural materialization obeys to a standardized ‘global’

typology. Added to the former, the paraphernalia of commercial, cultural

and political propaganda advertisements causes the visual culture

of our cities to be superior in impact, quantity and variety to that

of the role played by art institutions, whose purpose is the aesthetic

‘education’ and the shaping of a taste, a way of thinking

and a culture legitimized by the official histories of each community

and nation.

Santiago

de Compostella - PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

Santiago

de Compostella - PHOTO:

Ximena Narea |

At

first sight, it looks like a fight between a lion and a monkey,

since the total sum of museums, galleries, cultural centers

and some specialized institution is insufficient to counter

such a visual impact, because it represents a tiny percentage

in comparison with the omnipresence of all those other ‘institutions’

that today are necessary and essential, practically indispen-sable

elements of the urban mesh.

As a complement of this specific and variegated visual landscape

undergoing constant growth, one can hear musical groups on the

sidewalks, parks, gardens or squares. However, the majority

of those sounds don’t come from live music, but from cafeterias,

shops, bars, taxis and buses, which makes the urban environment

even more complex and crowded. Although this could seem like

something very characteristic for cities in the Caribbean region,

we can also find it on the ‘continent’: Lima, Panama

City, Caracas, São Paulo, Bogota, Bahia, Fortaleza, Managua.

For that reason, the everyday life in the open spaces of many

of our cities resembles a kind of carnival, a festival of images

and sounds, a spectacle not always subject to norms of organization

and design, which in the end alters our states of mind in a

silent, subtle and imperceptible way, our habits, our social

beha-vior, and our ways of ‘seeing the world’.

|

In Old Delhi, for example, one can inhale the

intense and penetrating smell of spices that immediately would make

one recognize the place one is walking on, added to the also unforgettable

amazement occasioned by the unrestricted access of cows on the public

streets. If we add the world’s only bird hospital to this, we

could shift from wonderment to delirium in an ins-tant. About the

smells, the same thing happens in some markets in the Golden Horn,

in Istanbul’s historic area, and in the harbor of Valparaiso,

where some of them mix with those produced by salts, birds and old

pieces of metal. In Addis Ababa, I remember a street in the beginning

of the 80’s christened by some foreigners to The Wall, not for

being a construction made with bricks, cement or steel: it was because

of the very strong and sharp and not so pleasant odor which literally

impeded traffic. One was forced to give up and take another route

in order to continue. Something similar occurs in the depressed alley,

popularly known as ‘El cartucho’ in down town Bogota,

although here one should add a touch of local violence never imagined

in the peaceful African city.

In the Casbah in Algiers, one of the fascinating

sites of the Islamic architecture and urbanism, it is not re-commended

to enter alone if one is a foreigner, given the real possibility of

getting lost and never being able to get out, or given the risk of

falling into the hands of local malefactors looking for an easy prey.

The same recommendation is made by the inhabitants of some barrios

in Rio de Janeiro, Medellin, Caracas (no way, pana, your friends will

tell you): all that belongs doubtlessly to the ‘image’

of the city.

Taking cabs and small buses in Santo Domingo,

Port of Spain or Fort de France is a unique experience in the Caribbean

due to the shock of the frantic music inside each vehicle, from which

it is only possible to recover a few minutes after having left the

car. In order to move from one place to another in Cairo, it is better

not to be in a hurry: more that 2 million taxis and urban buses traverse

the city day and night in the planet’s least signalized city,

and probably the noisiest one, where hardly 20 or 30 semaphores are

in working condition because of the fine dust from the nearby Sahara

desert. All this causes a generally accepted traffic chaos in which

every driver thinks he’s right.

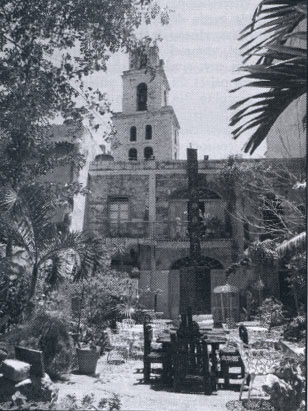

Patio

interior de un edificio en La Habana Vieja

Patio

interior de un edificio en La Habana Vieja

PHOTO:

Ximena Narea |

We live, then, in a state of environmental

alteration, sometimes of nice, ‘surreal’ or crazy,

other times, of more dramatic, confusing and exasperating

appearance. Both warn us that we are moving within a complex

and difficult universe of violent contrasts that are dynamic

in more than one sense, dominated by hidden forces of order

and, sometimes, of disorder. We have gotten ‘accustomed’

to both. It is the world where we are born and educated, and

it is also a source of a vast and wealthy cultural diversity

that we feel proud of in spite of the extreme economic conditions

in which it develops. Those urban cultures have given countless

signs of vitality, imagination, talent and energy, not always

acknowledged in other instances and scenes of the world, although

in the last decades an approaching to them has been taking

place. The bridges raised to and from our regions seem today

strong enough as to share that information, know-ledge and

emotions in both senses, and thus give birth to a new era

of universal understanding after hundreds of years of distance.

Good fortune is never too late, says one of our popular proverbs.

TWO

In Berlin, streets could be considered

perfect for tra-veling in vehicles: there are signalized footpaths,

cro-ssings, turns and circulations, and signs where the routes

to be followed are specified, as well as faraway and nearby

towns, important places, parking lots, dangerous passages

and obstacles. The sidewalks show clearly where the pedestrians

should walk and where the bicycles should transit, what places

are for functionally impaired persons, and where to find trash

bins or public phones. Each sign and symbol has been designed

by professionals who treat each and every one of these messages

rigorously, whether that might be for commercial establishments,

diners, coffee shops or places where one can listen to music.

Nothing is left to chance, spontaneity or improvisation.

|

In many other cities of Central and Eastern

Europe the same happens: their citizens move every day within an order

determined by laws and regulations, whose graphic expression in formal

terms corresponds to a universe of high economic development. The

commercial advertisement signs reach astonishing dimensions, in some

cases occupying the facades of buildings of many stories and are efficiently

adapted to the codes of today’s graphic design: good photographies,

efficient typography, simplicity and precision in the selected images,

and high resolution prints. The same thing happens with posters and

mural ads for culture and entertainment, though these are of smaller

dimensions.

In these European cities, there are norms forbidding

landlords and shop owners to surpass a certain level of decibel if

they wish to listen to music or produce any kind of sound. No one

is allowed to spontaneously transform the windows, doors and balconies

of their homes, or to intervene in the public space as they please.

On the other hand, squares, parks and green areas in the city show

countless sculptures, paintings, objects, interventions and urban

paraphernalia of remarkable beauty. The same happens with the show

windows in shops, bus and train stations and airports, whose level

of design surpasses that of other countries. The public space in which

millions of citizens circulate every day, from or towards their homes,

it is designed with the aim to guarantee their safety, comfort and

an efficient level of information.

Helsinki, Oslo, Stockholm, Copenhagen or Rejkavik,

are notorious examples of this integral environmental design. To some

this can seem exaggerated and dull, since not even the smallest architectonic

or urban detail escapes from the municipal authorities. Nothing is

‘put out of place,’ or dislocated in this little perhaps

radically cold and rational environment. The ‘perfection’

of this visual universe is such that, by contrast, many citizens in

these latitudes travel to our regions to enjoy ‘the other,’

that which could be called ‘the real-marvelous’ (a literary

way of pondering the juxtaposition and superimposition of codes and

visual signs, music, noise, chaos and poverty) that inhabits our cities

and regions, whose materialization, with local variations characteristic

of the context, can be found in Havana.

Basilea

/ PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

Basilea

/ PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

|

THREE

The question does not lie in elucidating what

form of inhabiting and living together is the best or the most pleasant,

because they respond to different socio-economic formations: something

that is so tangible and evident that we sometimes do not perceive

in its true dimension. Each one of these forms expresses the world

that created and upholds them. It is risky to affirm on which side

‘happiness’ or ‘life’ is. The millions of

inhabitants inserted in these urban dynamics have gotten used, to

live in and from them although temporally or even definitively, they

move to others. That happens frequently to professionals at various

levels and ranks, and even to artists. It seems that the ‘reason’

for this lies nowhere but in the complex rea-lity they face —

which is different in Europe, the United States, Africa, the Middle

East, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Facing it from the perspective of differences

might prove to be the most sensible way to help ourselves to understand

more objectively the art produced today in each one of our regions,

be it in areas consi-dered as ‘developing’ or in highly

industrialized countries that have started a slow process of ethnocultural

transformation as the result of visible migrations and the necessary

exchanges of this globalized universe.

FOUR

That world of images (and sounds, noises, odors,

street actions...) that populate the geography of our cities, inexorably

conditions the tastes, nourishes the imagination and molds the sensibilities.

From it, our artists extract many of the signs and referents to cons-truct

their works, since most of their concepts and ideas share the same

source. Those of us who are not artists (Joseph Beuys would not approve

of such statement), that silent majority of citizens is also conditioned

by a way of ‘seeing,’ not only the world that surrounds

us, but also other worlds beyond our noses. To this we could add —

and it would make this story longer — the fashion that every

citizen adopts according to his preferences and means, as well as

many other factors (cars, trucks and buses circulating by day and

by night, the illumination of streets and public places) until we

achieve an exhaustive analysis, but here I limit myself to those belonging

or being associated to the visual, being re-appropriated as signs

and symbols by the artists from within their territories, in may cases

with the support of curators and institutions, specially when it has

to do with cultural events, of big or small impact.

Our cities, towns , villages and hamlets generate

a kind of visual culture in some ways different to the one we could

find in other urban settings where any ambulant activity hardly exists,

informal economy, illegal appropriations of public spaces, abundant

ruins, settlements illegally constructed with poor materials, and

undiscriminated advertisement. It is about, once again, a contextual

problem, a problem of daily influences of that urban culture on the

citizens, which has represented a never ending source for our artists

during the last years, as it can be confirmed in Brazil, Mexico, Chile,

Puerto Rico, Belize, Cuba, Colombia, South Africa, Angola, Nigeria,

Thailand, Indonesia, the Phili-ppines and China.

Berlín

/ PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

Berlín

/ PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

|

It

is no longer only ‘the big narratives’ that are the cause

of many valuable works in our regions (from history, social movements,

politics to ideologies, gender and race issues). Now, even certain

areas of eve-ryday life, of the intricate mesh of messages upon which

we stumble every day in the streets, of the quotidian challenges that

the old and new economic structures submit us to, and of our share

of dreams and aspirations. We face an objective and subliminal bombardment

of visual codes — far superior in quantity to that attributed

to certain electronic communication media — which become visible

to the eyes and sensibilities of our artists.

Hence the more active participation of our creators on and upon the

urban environment, independently from their scale and signification,

since the cities have become the largest and most exciting galleries

for the circulation of works, and a space for the confrontation and

reflection upon their fortune and their destiny. Many wish to contribute

from their tiniest parcel to shed light (be it from parody, criticism

or adulation) of those ongoing transformations taking place in buil-ding

blocks, parks, streets and squares.

Art

seems thus engaged in the return to one of its places of origin, to

the recovering of the role played by the community and the city in

human history, long before it was subdivided into functions and classes.

It is a trip to the seed, postponed by a span of centuries. The eternal

return.

Belgrad

/ PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

|

FIVE

There are as many urban cultures as specific

realities in each city, country and region. I have attempted here

to underline those where perhaps more ample margins exist for disordered,

non-regulated interventions; that is, where non-professionals participate,

even when they do not produce a sufficient amount of visual and non-visual

images. This could be called urban popular culture, in its wider sense.

But it is hardly ever mentioned, since it is not produced from within

the territories legitimated and sanctified by art historiography and

criticism: many of its creators are not sufficiently known, their

‘works’ escape the traditional analysis and studies in

spite of the massive volume they occupy within the physical space

where they are produced and of their undeniable influence on everyday

life.

From their own territories, and perhaps from

other more distant ones, various ar-tists reflect upon them from a

critical pers-pective with the aim of calling the attention of the

public and contribute to their improvement, whereas other exalt some

of its traits as an important factor in the identity of a city, or

of a small or big urban conglomerate. And an event such as the Biennial

of Havana puts them in circulation within an open system of artistic

proposals and exhibits, integrates them in its structure and organization,

and shows them to a public, perhaps captive of the splendid and effective

spider webs of a post modernity that has not done enough justice to

them, still busy privileging other expressions closer to the market,

to the controversial dictates of an international contemporary curatorship

and to the ‘tyranny of the museums.’ However, they continue

to be fundamental and profound ingredients of our identity at the

environmental, cultural and social levels, and the Biennial of Havana

doesn’t refrain from insisting on any of the aspects that could

shed light on our lives and destinies, even at the risk of repeating

ourselves.

Copenhague

/ PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

Copenhague

/ PHOTO:

Ximena Narea

|

We are thus still engaged in trying to identify our

various identities and faces, because they are many, perhaps too many.

While many think they know us thanks to the achievements

of certain humanistic disciplines and sciences, we discover with preoccupation

and enthusiasm those elements that have been poorly visible to our

own eyes and hearts.

There are those who think they know everything, or

almost everything, about themselves: happy them.

We think that we do not know enough about this entangled

visual, cultural mesh underlying our cities except for ‘that’

shown every day by the television and the newspapers.

It is about this so exciting and polemic phenomenon

that we pronounce ourselves in an international event that must aspire

to serve to the exchange of ideas and human beings in spite of the

serious economic strains we are going through.

(Note by the author: this text is a barely modified version of the

original, published in the General Catalogue of the ninth edition

of the Biennial of Havana, in March-April 2006.)